Many years ago I became acquainted with Catherine Austin Fitts, while both of us were members of what was then called a listserv, which was managed by Kris Millegan. The three of us and many others were trying to learn how the American economy incorporated proceeds of narcotics sales into our financial system. Sometime after Catherine had visited me in Texas, the Texas corporation Enron collapsed in November 2000, the same month George W. Bush was first elected and less than a year before the September 11, 2001 destruction of the World Trade Center. (See James P. Galasyn's Bush/Enron Chronology).

The work below grew out of those debacles.

ENRON

From Hoover’s Handbook of American Business, 1993:

Enron traces its history through two well-established natural gas companies — InterNorth and Houston Natural Gas (HNG).

InterNorth started out in 1930 as Northern Natural Gas, an Omaha, Nebraska, gas pipeline company. By 1950 Northern has doubled its capacity and in 1960 started processing and transporting natural gas liquids. The company changed its name to InterNorth in 1980. In 1983 it spent $768 million to buy Belco Petroleum, adding 821 billion cubic feet of natural gas and 67 million barrels of oil to its reserves. At the same time the company (with four partners) was building the Northern Border Pipeline to link Canadian producing fields with U.S. markets.

HNG, formed in 1925 as a South Texas natural gas distributor, served more than 55,000 customers by the early 1940s. It started developing producing oil and gas properties in 1953 and bought Houston Pipe Line Company in 1956. Other major acquisitions included Valley Gas Production, a South Texas natural gas company (1963), and Houston’s Bammel Gas Storage Field (1965).

In the 1970s the company started developing offshore fields in the Gulf of Mexico, and in 1976 it sold its original gas distribution properties to Entex. In 1984 HNG, faced with a hostile takeover attempt by Coastal Corporation, brought in former Exxon executive Kenneth Lay as CEO. Lay refocused Enron on natural gas, selling $632 million of unrelated assets. He added Transwestern Pipeline (California) and Florida Gas Transmission, and by 1985 Enron operated the only transcontinental gas pipeline.

In 1985 InterNorth bought HNG for $2.4 billion, creating the U.S.’s largest natural gas pipeline system (38,000 miles). Soon after, Kenneth Lay became chairman/CEO of newly named Enron (1986), and the company moved its headquarters from Omaha to Houston.

Laden with $3.3 billion of debt (most related to the HNG acquisition), Enron sold 50% of Citrus Corporation (operated Florida Gas Transmission, 1986), 50% of Enron Cogeneration (1988), and 16% of Enron Oil & Gas (1989). In the meantime the company paid $31 million for Tesoro[1] Petroleum’s gathering and transportation businesses in 1988.

In 1990 the company bought CSX Energy’s Louisiana production facilities, which helped to increase Enron’s production of natural gas liquids by nearly 33%. In late 1991 Enron closed a deal with Tenneco to buy that company’s natural gas liquids/petrochemical operations for $632 million.

Enron’s 1992 contract with Sithe Energies Group to supply $4 billion worth of natural gas over 20 years to a planned upstate New York cogeneration plant fits its vision of natural gas as a leading fuel for the future.

History of Enron, Originally Founded as

Houston Natural Gas Company

In 1893 John Henry Kirby started construction of the Gulf, Beaumont and Kansas City railroad line, which he sold to the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe in 1900. He decided to invest the money he made on building the railroad into East Texas timber land, but after the big Spindletop oil discovery near Beaumont in East Texas in 1901, he took another turn into oil exploration. With dollar signs in their eyes, however, his creditors thought it more advantageous for themselves to take the corporate assets held as security than to give Kirby the necessary time to develop those assets into oil-producing property.

On July 6, 1901 the Houston Daily Post contained a huge front page headline and photo of Kirby announcing the chartering of Houston Oil Company of Texas with a capitalization of $30 million and of the Kirby Lumber Co. with $10 million in capital. The stock was issued, but Kirby still had to obtain buyers for the stock. That means he had to find stock brokers who had connections to huge pools of capital to invest. For his financing, Kirby had gone to Patrick Calhoun, a New York corporate attorney "with desirable connections in eastern banking circles." Calhoun was the grandson of John C. Calhoun, vice-president under John Quincy Adams.

Patrick Calhoun, a native of South Carolina, owned stock in the Southern Oil Co., which had 100 producing oil wells in the Corsicana Field in East Texas. The investors Calhoun brought into Kirby's companies included Brown Brothers of New York; Simon Borg & Co., originally founded in Tennessee; and Maryland Trust Co. of Baltimore, the latter being proposed as trustee to handle the company's securities and act as its subscription agent. Maryland Trust Co. was headed at that time by ex-Confederate officer, Colonel J. Wilcox Brown.

The Brown Brothers firm was founded in the United States by descendants of Alexander Brown, who also were involved in the English brokerage firm of Brown & Shipley, of Baltimore, Maryland, and, after 1825, in New York. Brown Brothers would operate out of New York City until its eventual merger in 1931 with W.A. Harriman & Co., the latter an investment bank set up five years earlier for E. H. Harriman's young sons by Prescott Bush's father-in-law, George Herbert "Bert" Walker of St. Louis, Missouri, who is the subject of a series of articles at this blog.

Foreclosure and Receivership

The financing scheme for the Kirby companies was an intricate system of cross-collateralization which Kirby alleged was designed to allow the creditors to steal the assets of his companies. Receivers were appointed on February 1, 1904, the same day interest was due on timber certificates that had originally been issued for $11 million, but devalued down to $7 million. Of that, $6 million work of the certificates had been sold by Brown Brothers, while being guaranteed by Houston Oil Co.[2] The semi-annual payment was made by Brown Brothers & Co. in the amount of $700,000, including $210,000 interest, but only the interest was tendered to Maryland Trust, which was rejected.

The receivers appointed for Houston Oil were F.A. Reichardt, cashier of Planter's and Mechanic's National Bank of Houston (of which John H. Kirby was president) and Thomas H. Franklin, a San Antonio attorney, who was president of the Houston Oil Company. N.W. McLeod, a "prominent St. Louis lumber man," and B.F. Bonner, Kirby Lumber Company's vice president, who lived in Houston, were appointed as receivers for Kirby Lumber.[3]

A receiver not mentioned in the New York Times article at that time was Col. J.S. Rice, who, according to his obituary in the Houston Chronicle on March 12, 1931, had been in the sawmill business in Tyler since 1881, after starting as a clerk at the Houston & Texas Central Railroad in 1879 — a railroad extending west and north from Houston to the cotton fields of central Texas. Jo Rice served as receiver of Kirby Lumber from 1904 to 1909 and was elected vice president after it was reorganized. He was also president for a time of Great Southern Life Insurance, vice president of Houston Land Corp., and a director of Missouri Pacific Railroad Co. A nephew of William Marsh Rice, through marriage he was also related to both W.S. Farish and Stephen P. Farish--two brothers who had married Libbie Randon Rice and Lottie Rice, respectively, Jo Rice's sister and cousin.

The New York Times quoted Mr. Kirby as saying that both companies were profitable, and "the only and sole cause of the present trouble lies in the fact that the securities issued the Houston Oil Company have not been marketable." The Times went on to say that

... interests identified with the Atchison and with the St. Louis and San Francisco [Frisco] Railroads have a large interest in the Kirby Lumber Company. Representatives of several banking houses more or less closely associated with the two companies which have just been placed in receivers' hands said yesterday that the assets of the companies were of undoubted value, and that the proceedings were really the outcome of internal discord.[4]

From the Galveston Daily News, February 4, 1904:

On February 12, 1904 the New York Times contained a short item on page 14 stating that a committee of five had been chosen by the holders of the 6% timber certificates issued by Maryland Trust--George W. Young, Dumont Clarke (president of the American Exchange National Bank in New York and a director of U.S. Mortgage & Trust Co.), James Brown (chairman of Brown Brothers), Gerald L. Hoyt (who served as a director of the Wisconsin Central Railroad alongside Brown Brothers partner, John Crosby Brown), and F.S. Smithers. A week later, Kirby was again quoted in the Times, as follows:Houston, Tex., Feb. 3 --There was nothing new here today in connection with the affairs of the Kirby Lumber Company or the Houston Oil Company, both of which were given receivers by Judge McCormick of New Orleans. Affairs about the Planters and Mechanics National Bank moved along today as they do every day. There was no unusual deposit nor unusual withdrawal of money. In other words, they had their normal appearance all day. In connection with the affairs of the appointment of the receivers the following facts and figures show the status:

The Kirby Lumber Company was incorporated under Texas laws in July, 1901, capitalized at $10,000,000. Its object was to take over fifteen sawmills previously purchased by the Houston Oil Company of Texas. Financial aid was obtained from Eastern associates also interested in the Houston Oil Company of Texas, capitalized at $30,000.000. Stock of the Kirby Lumber Company is divided into $5,000,000 of common, and preferred shares of the same amount. The Kirby Lumber Company contracted with the Houston Oil Company for six and one-half billion feet of yellow pine timber of 12 inches diameter and upward, for the aggregate sum of $30,000,000, to be paid in semi-annual installments in sixteen years....The company owns 180,000 acres of land at Kountze easily worth $5,000,000. Other lands held by the company amount to 127,220 acres, readily marketable for at least $3,000,000.

The temporary receivers of the Kirby Lumber Company and the Houston Oil Company have ordered a continuance of operations in the usual manner, and announcement is made that plans are being considered to terminate the receiverships when the cases are called before Judge Burns of the Southern District of Texas on February 17.

"A distinguished Wall Street operator undertook to finance the Houston Oil Company; had and exercised undisputed authority in the conduct of its affairs. He also directed the financial affairs of the Kirby Lumber Company until about a year ago, and during this period of his control caused the latter company to invest heavily in the preferred shares of his oil company....The Board of Directors of the Houston Oil Company, over the protest of the Wall Street promoter, who is still a member of the board, voted to accept the money and to request the Maryland Trust Company not to proceed, but the money was declined and the demand for receivership persisted in."By the end of March of that year a lawsuit had been filed by members of a stock syndicate managed by two officers of the Baltimore Trust and Guaranty Company alleging misrepresentations made about the condition of the lumber company in the prospectus. The petition further alleged that one month prior to the appointment of receivers, Kirby formed a holding company with Benjamin F. Yoakum, president of the St. Louis and San Francisco Road, to which they transferred the majority of the Kirby Lumber Company stock, and that they formed the Houston, Beaumont and Northern Railroad Company, to which Kirby Lumber's traction lines and other railroad properties were transferred. In addition, the HB&N RR Co. was capitalized at $500,000 with a bond issue of $1 million. Yoakum loaned the company $600,000 and in return received all the bonds, half the stock and $18,000 in commissions. The newly formed company used half the loan proceeds plus an additional $18,000 to repay a prior loan to Yoakum and his commission for this loan.[5]

Surprisingly, we learn that in 1904 Yoakum was a director and on the executive committee of the board of Seaboard Air Line railroad with people very close to the Alex. Brown bank, including Sol Davies Warfield, uncle of Wallis Simpson and others written about in another blog this author writes.

In 1906 Walter Monteith, brother of Edgar Monteith, Sr. (who many years later became attorney for Gibraltar Savings and Brown & Root), was appointed to act as receiver on behalf of the investors.[6] A settlement was reached in 1908. Houston Oil owned several shallow oil wells in Nacogdoches County, all of the stock of Southwestern Oil Co. and properties of Southern Oil Co., as well as stock in Higgins Fuel and Oil Co., but for revenue it primarily relied on the stumpage agreement with Kirby Lumber. Because of more efficient equipment and the demand for timber for the railroad industry, the lumber company was better able in the next few years to meet its contract requirements, and virtually the same investors organized Houston Natural Gas Co. (HNG) in 1926.

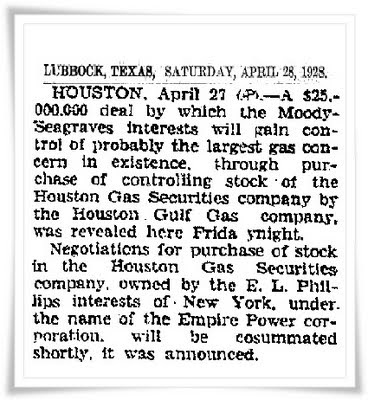

Houston Pipe Line Co. was a wholly owned subsidiary of Houston Oil Company of Texas, and its stockholders formed HNG as a separate corporation a year before the pipe line company completed constructing distribution gas lines. Their hope was to compete with Houston Gas and Fuel (HG&F), of which Captain James A. Baker was president. HG&F had signed a contract to buy only from Houston Gulf Gas, and HNG therefore turned to the outlying areas and other cities in Harris County for customers. Shortly before the stock market crash in 1929, Houston Gulf Gas bought out HG&F and then merged with United Gas Corporation, a holding company, 42% of which was bought by Pennzoil (Zapata’s successor) in 1965, then divested by the SEC in 1970, creating a separate investor-owned corporation, United Gas, Inc.--later Entex. The two gas companies merged in 1976 and were later merged into Enron.

[NOTE: The money can be followed directly from the Baker network into Enron.]

- E.H. Buckner, president - 70 shares

- Louis Seymour Zimmerman, Baltimore (president of Maryland Trust Co.) - 70 shares

- George Mackubin, Baltimore - 70 shares

- David Hannah, Houston - 40 shares

- Judge H.O. Head, Sherman, Texas - 40 shares

- McDonald Meachum, Houston - 40 shares

- C.B. McKinney, Houston - 40 shares

- H.M. Richter, Houston - 40 shares

- George A. Hill, Jr., Houston (father of Raymond M. Hill—discussed in Pete Brewton’s book, The Mafia, the CIA and George Bush) - 35 shares

- T.M. Kennerly, Houston - 35 shares

- A.S. Henley, Houston - 20 shares

The following May, 1926, 1,500 additional shares were issued, with 140 each bought by the largest three investors, with Hannah and McKinney each buying 80 more. New shareholders of note were Samuel C. Davis (80), Thomas S. Maffit (80), John Foster Shepley (80), Samuel W. Fordyce (80), and N.A. McMillan (70), all of St. Louis, Missouri--part of the syndicate for which Prescott Bush's father-in-law, George Herbert "Bert" Walker, was already handling investments through his investment bank, G.H. Walker & Co.[7]

After the 1926 sale of stock, the following geographical breakdown existed:- Houston -- 1,100

- Baltimore -- 430

- St. Louis -- 390

- John H. Duncan (also a member of the audit committee)--chairman of the board of Gulf Consolidated Services, Inc. in Houston and chairman of the executive committee of Gulf + Western Industries, Inc. in New York--since 1968, who owned 40,000 shares of HNG.

- C. Thomas Clagett, Jr. (also a member of the audit committee), whose occupation was investments in Washington, D.C.--who owned 252,226 shares individually plus over 700,000 additional shares as trustee for family members.

- J.A. Edwards, a board member since 1968, who was president of Liquid Carbonic Corp., an HNG subsidiary (42,596 shares).

- W.S. Farish III, who was shown to be president of Fluorex Corp., an "international mineral and exploration company" in Houston (4,000 shares), grandson of Libbie Rice Farish.

- Robert R. Herring, chairman and CEO of HNG, director since 1964 (60,000 shares), husband of Charlie Wilson's girlfriend, Joanne Herring.

- M.D. Matthews, vice-chairman of board (32,482 shares).

- Neil D. Naiden, partner of Morgan, Lewis & Bockius, a Washington, D.C. law firm.

- Charles Rathgeb, chairman and CEO of Comstock International, Ltd. in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Interestingly enough, Robert Herring (at the time of his death married to a Houston "socialite," the former Joanne Johnson King) was also president of Rice University in 1980, shortly before his death, and John Duncan's brother, Charles Duncan, Jr., retired in 1996 as chairman of the Rice board, which had previously been headed by George Rufus Brown, brother of Herman Brown, co-founder of Brown & Root (later Halliburton).

HNG located its offices in 1927 in the Petroleum Building built by Irishman J.S. Cullinan, where it remained until 1967, when it became the core tenant of Kenneth Schnitzer's office building at 1200 Travis. The primary attorney for the company was shareholder George A. Hill--of Kennerly, Williams, Lee, Hill & Sears--the father of Raymond Hill of Mainland Savings fame, to whom Pete Brewton devoted an entire chapter of his book. The foremost Houstonian shareholder was David Hannah who had arrived in Houston from Scotland in 1908 and was head of the Houston Cotton Exchange for a time. David Hannah Jr. would later be named a trustee of the Hermann Hospital Estate and serve alongside Walter Mischer, Jr. He would also attract investment from Toddie Lee Wynne, Jr. into a company called Space Services, Inc., which would launch the first private satellite into space from Matagorda Island, Texas.

In 1956 Houston Oil Co. was sold to Atlantic Refining Co. for a quarter-billion dollars ($250 million). In 1966 Atlantic acquired Richfield Oil Corp., a company which had been placed in bankruptcy in 1928 when it had over $10 million in judgment claims resulting from canceled oil leases at the Elk Hills Naval Reserve, subject of the Teapot Dome scandal, to Pan American Petroleum, received by Richfield from Edward L. Doheny in 1928. The case was settled in 1933 for $5 million after broker Henry L. Doherty & Co. (60 Wall Street) made an exchange offer for 4 shares of Richfield for one share of Cities Service Co. stock. To protect its interest in the stock, Cities later purchased a large block of Richfield and Pan American bonds.

It appears that these various oil companies owed interest on bonds to holders comprised of numerous foreign, mostly British, investors. According to a book written in 1972 by Charles S. Jones,[8] the former chairman of Richfield, as his very first act, once the decision was made to merge with Atlantic, was:

|

| The newspaper misspelled the name of Pakistan's President--Zia ul Haq. |

In 1956 Houston Oil Co. was sold to Atlantic Refining Co. for a quarter-billion dollars ($250 million). In 1966 Atlantic acquired Richfield Oil Corp., a company which had been placed in bankruptcy in 1928 when it had over $10 million in judgment claims resulting from canceled oil leases at the Elk Hills Naval Reserve, subject of the Teapot Dome scandal, to Pan American Petroleum, received by Richfield from Edward L. Doheny in 1928. The case was settled in 1933 for $5 million after broker Henry L. Doherty & Co. (60 Wall Street) made an exchange offer for 4 shares of Richfield for one share of Cities Service Co. stock. To protect its interest in the stock, Cities later purchased a large block of Richfield and Pan American bonds.

It appears that these various oil companies owed interest on bonds to holders comprised of numerous foreign, mostly British, investors. According to a book written in 1972 by Charles S. Jones,[8] the former chairman of Richfield, as his very first act, once the decision was made to merge with Atlantic, was:

... to go to London to visit my friend Sir Maurice R. Bridgeman, chairman of British Petroleum. While his company was very much interested in entering the United States market, British Petroleum needed government approval to use dollars, and Sir Maurice thought the market value of British Petroleum shares too low for an advantageous exchange of stock. The matter was left in abeyance until either party desired to explore it further.Jones next offered to merge with K.S. "Boots" Adams--father of former Houston Oilers owner "Bud" Adams--who was chairman of Phillips Petroleum. Later, he set up talks with Standolind at Bunny Harriman's ranch in southeastern Idaho, "Railroad Ranch."[9] After news of this meeting was leaked by unknown sources, Richfield's stock increased, leading to an offer from Robert O. Anderson, chairman of Atlantic of Philadelphia, whom Jones met in August 1965, again at the Harrimans' ranch, leading one to believe that Brown Brothers had a big interest in a buyout of Richfield. After that meeting several other companies expressed an interest, but, according to Jones, "a curious event occurred."

One of our Washington lawyers called to tell me that a Mr. Cladouhos, an Antitrust Division lawyer assigned to the case, had suggested that Richfield settle the suit by merging with Atlantic Refining Company. The division had earlier suggested a merger, but this was the first time it had named a partner. The suggestion seemed most unusual, but I concluded that Bob Anderson's lawyers had probably been exploring the Justice Department's attitude toward a merger with Richfield and had thus given Cladouhos this particular inspiration.When the merger was finally worked out, "Francis Kernan and others of the Boston-based investment bank, White, Weld & Company, represented Richfield."[10] The White, Weld investment bank, which in 1974 merged with G.H. Walker and Co., owned by then by G.H.W. Bush’s Uncle Herbie, his own financial patron. The White Weld-Walker amalgam also merged its London and Swiss operations with Crédit Suisse, the premier drug-money-laundering institution of the day, and the domicile for the Bush-North "Enterprise" offshore bank accounts.

As far back as 1959, when W. Alton Jones was still living, we had made a study of the possibility of merging Richfield, Sinclair, and Cities Service to form a national company strong enough to compete with the international majors. There was always the imponderable of the Justice Department's attitude, but we decided that we would never know the reaction until we tried....Cities Service already owned about 30 percent of Richfield.

The Zimmerman who was named as a HNG shareholder was president of Maryland Trust from 1910 until 1930, when the company merged with Drovers and Mechanics National Bank and the Continental Trust Company, but continued to operate under the name of Maryland Trust, with Zimmerman as senior vice president until his retirement in 1948. Shareholder Mackubin was a senior partner in the brokerage firm of Mackubin, Goodrich & Co. and became a director of Houston Oil Co. in 1925.

Continental Trust was operated by Solomon Warfield, the uncle of Wallis Simpson —Duchess of Windsor. Solomon Warfield acquired a number of shares of Alleghany preferred stock, "issued in a storm of controversy by the banker J.P. Morgan, who was a chief investor for King George VI and Queen Elizabeth at the time they were Duke and Duchess of York," for his niece, which she inherited upon his death in 1927. This stock had always been her "first investment favorite," according to her biographer Charles Higham.[11] When the Duke and Duchess became friends with Alleghany’s Robert Young, allegedly after being introduced by mutual friend Robert Foskett after the Windsors moved to the Bahamas, Young and his wife Anita became one of their few close friends. Both Foskett and Young were directors of Alleghany and lived in Palm Beach, Florida. When Warfield died, he left her only "the interest from $15,000 worth of shares in his railroad companies and in the related Alleghany Company and in the Texas Company [later Texaco]. She had expected a slice of his $5 million, and she furiously began a lawsuit against the trustees of the estate, in the form of a caveat."[12]

This leads one to wonder whether George and Herman Brown really owned Brown & Root, or whether they were primarily nominees for someone else, or whether they were simply very dependent upon the other capital invested in their corporations--all of them handled by the investment bank of Dillon Read, specifically by August Belmont IV, thought to be working on behalf of his patron, Rothschild Bank, which handled American investments for royal British capital. George and Herman were nobody before 1942, but almost overnight George Brown became Lyndon Johnson's chief financier and a director of major multi-national corporations, and for many years served as chairman of Rice University. After the death of Herman Brown, Brown & Root would be sold to and become a subsidiary of the Halliburton Company, the company to which Vice-President Dick Cheney is so closely tied. The sale proceeds set up the Brown Foundation, managed by, among others, Edgar Monteith and Fayez Sarofim, the investor/husband of Herman Brown's adopted daughter, Louisa Stude.

Sarofim was born in Egypt, but obtained a bachelor’s degree in food technology from the University of California and an MBA from Harvard Business School. In 1958 he established Fayez Sarofim & Co. in Houston, though his first job in Texas was in the Abilene branch of Anderson Clayton cotton merchants, where he became close to Edward Randall III and his circle of friends. Herman Brown's adopted daughter Louisa Stude was in the same circle. After their marriage, Herman Brown's new son-in-law began managing the corporate retirement fund for Brown & Root and the endowment of William Marsh Rice University, then valued at $63 million. Herman himself died in 1962, and Sarofim thus stepped up in managing a big part of the Brown & Root wealth.

Entex was the successor corporation to Houston Gas & Fuel formed by Captain James A. Baker of Baker, Botts probably for his major client, the Rice family or Rice Institute itself. Baker was president and had signed a contract to buy only from Houston Gulf Gas, preventing any competition in its market from upstart company, Houston Natural Gas, which was forced to market its product outside the city of Houston. Eventually, HG&F merged into Houston Natural Gas in 1976, and later became Enron.

If all the original shareholders retained their shares in the initial companies, Enron would be controlled by the families of the Rices, Farishes and the stockholders of the Maryland Trust Co., which put John Henry Kirby in receivership in the early days of the 20th century. But of course people do sell their stock or die and pass it along to heirs and devisees. Nevertheless, it would be fascinating to see who the major stockholders in Enron were in 2001 when it cratered, and took so much with it, only a matter of days following the destruction of the World Trade Center Buildings in New York on September 11.

Originally published at this blog on May 3, 2011 as

"Pakistan's old friend, Joanne Herring of Houston."

ENDNOTES:

[1] Tesoro Petroleum Corporation, has an equally fascinating history as Enron, as seen from this excerpt from 1965: "There's some local confusion over the proposed stock interchange of Coronet Petroleum Corp. of Houston and the Texstar Corp. of San Antonio. Coronet is the former Gulf Coast Leaseholders, Inc. Texstar is the holding company organized a decade or so ago by the late Tom Slick of San Antonio, and purchased last year by Amon Carter Jr., of Fort Worth, and others. William T. Rhame of San Antonio is president of Texstar. Burford King, Fort Worth who became president of Gulf Coast Leaseholds before its name was changed to Coronet last year, was one, of those listed as the purchasers of the old Slick firm. Then, reportedly, the [Amon] Carter group sold its Texstar stock to Gulf Coast and this group became the controlling interest of the Texstar Corp. All this was last summer. In the fall, Bob West of San Antonio, who had been head of the Texstar Petroleum Corp., subsidiary of the corporation of the same name, set up his own company and purchased the petroleum subsidiary from the parent corporation. West's new company is Tesoro Petroleum Corp. Now, Coronet Petroleum stockholders will meet April 15 in Houston to vote on an agreement whereby Texstar Corp. would assume control of Coronet Petroleum stock. The ratio would be one share of Texstar stock for each 5.8 shares of Coronet stock. As of Jan. 1 Tex Star Oil & Gas Corp. of Dallas changed its name to Texas Oil & Gas to avoid confusion in the public's mind over it and the Texstar Corp. of San Antonio. Louis Becherl Jr., of Dallas heads this firm which has no connection with Texstar Corp." [Source: San Antonio, TX EXPRESS/NEWS - April 4, 1965]

[2] New York Times, February 2, 1904, p. 11.

[3] New York Times, February 3, 1904, p. 11.

[4] New York Times, February 3, 1904, p. 11.

[5] New York Times, March 30, 1904, p. 12.

[6] It should be noted that both George and Herman Brown and the Monteiths previously hailed from Bell County, where several surveys of land were patented to a Monteith. It might be interesting to learn whether the Browns may have been related to the family of brokers.

[7] Samuel Davis, born in 1871, was a son of John Tilden Davis, and his brother was none other than Dwight Filley Davis for whom the Davis Cup was named. When he obtained a passport in 1918, Samuel Craft Davis called himself president of the John T. Davis Estate and stated he was traveling to France and England to work on behalf of the YMCA's War Work Council. More will be said about his family and about John Foster Shepley in future posts at this blog.

[8] Charles S. Jones, From the Rio Grande to the Arctic : The Story of the Richfield Oil Corporation (Norman, Okla: Univ. of Okla. Press, 1972), p. 308.

: The Story of the Richfield Oil Corporation (Norman, Okla: Univ. of Okla. Press, 1972), p. 308.

[9] Remarkably it was in Sun Valley, the Harrimans' ski resort, where Warren Buffet and Disney's chairman bumped into each other accidentally and decided to merge.

and Disney's chairman bumped into each other accidentally and decided to merge.

[10] Keep in mind that at that time, the Hannah family appeared to be major shareholders of Houston Natural Gas. David Hannah was also chairman of a private company competing with NASA, with a land development company with a Scottish name, and with an amusement company started near the Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport in 1955 by Robert Bernerd Anderson, trustee of the Waggoner estate, lawyers Toddie Lee and Angus Wynne, who wanted Bill Zeckendorf to help develop as an industrial and distribution center. Zeckendorf brought in the Rockefeller Brothers' investment company. Angus Wynne was the father of Bedford Wynne, who was not only an employee of the Murchison family, but a minor partner with Clint W. Murchison, Jr. in the Dallas Cowboys football team.

[3] New York Times, February 3, 1904, p. 11.

[4] New York Times, February 3, 1904, p. 11.

[5] New York Times, March 30, 1904, p. 12.

[6] It should be noted that both George and Herman Brown and the Monteiths previously hailed from Bell County, where several surveys of land were patented to a Monteith. It might be interesting to learn whether the Browns may have been related to the family of brokers.

[7] Samuel Davis, born in 1871, was a son of John Tilden Davis, and his brother was none other than Dwight Filley Davis for whom the Davis Cup was named. When he obtained a passport in 1918, Samuel Craft Davis called himself president of the John T. Davis Estate and stated he was traveling to France and England to work on behalf of the YMCA's War Work Council. More will be said about his family and about John Foster Shepley in future posts at this blog.

[8] Charles S. Jones, From the Rio Grande to the Arctic

[9] Remarkably it was in Sun Valley, the Harrimans' ski resort, where Warren Buffet

[10] Keep in mind that at that time, the Hannah family appeared to be major shareholders of Houston Natural Gas. David Hannah was also chairman of a private company competing with NASA, with a land development company with a Scottish name, and with an amusement company started near the Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport in 1955 by Robert Bernerd Anderson, trustee of the Waggoner estate, lawyers Toddie Lee and Angus Wynne, who wanted Bill Zeckendorf to help develop as an industrial and distribution center. Zeckendorf brought in the Rockefeller Brothers' investment company. Angus Wynne was the father of Bedford Wynne, who was not only an employee of the Murchison family, but a minor partner with Clint W. Murchison, Jr. in the Dallas Cowboys football team.

If this director was actually oilman, Robert O. Anderson (as distinguished from Eisenhower Treasury Secretary Robert B. Anderson), it is interesting to explore this link between him, David Hannah and the Wynnes, since he would also add into the mix a connection with John Dick and Walter Mischer.

Mischer's connection to Robert O. Anderson involves a 250,000-acre ranch near Big Bend National Park that Mischer owned with Anderson. According to Pete Brewton, John Dick "had Anderson over to his house for dinner, while Anderson invited Dick to his annual Christmas dinner for the 'world's most powerful men' at the Claridge Hotel in London. The only woman in attendance . . . was then-British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher." Brewton, p. 274. Both Mischer and John Dick also both borrowed money from Hill Financial Savings of Pennsylvania, one of the companies involved in the St. Joe Paper transaction. Anderson's father was Hugo A. Anderson, a leading oil and gas banker at First National Bank of Chicago. When Robert O. retired from AtlanticRichfield, he went into an oil and gas partnership with Tiny Rowland, considered by some to be a front for the British monarchy. In 1975 HNG directors included John H. Duncan and W.S. Farish III. In 1976 the company merged with Entex and later with Enron.[11] Charles Higham, The Duchess of Windsor: The Secret Life (New York: Charter Books, 1989), p. 387.

[12] Higham, p. 67.

[13] Wechsburg, p. 248.

in Charlie Wilson's War and was played on the screen by Julia Roberts. After her romance with Wilson, she later married a rich businessman named Davis.

in Charlie Wilson's War and was played on the screen by Julia Roberts. After her romance with Wilson, she later married a rich businessman named Davis.

, who controlled the Cadillac Fairview Company mentioned earlier. She (along with a number of investors named Loeb, Kempner, Levin, Cohen and Gimbel with Park Avenue, New York addresses) was a partner in a joint venture called GIX Associates with Gulf Interstate Exploration Co. of Houston and Norco Investments Co. of Washington, D.C. in 1983. Norco (perhaps coincidentally) is the name of a refinery in New Orleans owned at one time by Shell Oil. In Stephen Birmingham's book, Our Crowd, he states:

, who controlled the Cadillac Fairview Company mentioned earlier. She (along with a number of investors named Loeb, Kempner, Levin, Cohen and Gimbel with Park Avenue, New York addresses) was a partner in a joint venture called GIX Associates with Gulf Interstate Exploration Co. of Houston and Norco Investments Co. of Washington, D.C. in 1983. Norco (perhaps coincidentally) is the name of a refinery in New Orleans owned at one time by Shell Oil. In Stephen Birmingham's book, Our Crowd, he states:  , which has assets of some $300 million. Edgar Bronfman, now [1967] in his middle thirties, and head of his father's American subsidiary, Joseph E. Seagram & Sons, joined the board of directors of the Empire Trust Company in 1963. . . .[3]

, which has assets of some $300 million. Edgar Bronfman, now [1967] in his middle thirties, and head of his father's American subsidiary, Joseph E. Seagram & Sons, joined the board of directors of the Empire Trust Company in 1963. . . .[3]